Jefferson Scott

Intelligent Christian Thrillers

Operation: Firebrand—Crusade

Prologue

The sun should rise differently if it is to be a day of death.

But it doesn’t.

Anei woke when her brother, Mabior, slipped out of the tukul to milk the cows. It was still dark, but Anei could see her mother sitting up, nursing little Ajok. Her father, her Wa, was snoring softly.

The air was cool and her mat was warm. But Anei was a Dinka girl approaching marriageable age and she knew her place. She stood, pulled her red robe over one shoulder, and stepped out into the village.

Stars still punctured the black cloth sky, but milky orange light was already spilling across it from the east. The thatched roofs of the round tukuls grew distinct in her vision. The cows in the large pen to her right complained about the milking and Anei heard grumpy boys doing their chores. Anei’s nose complained, too, about the stench of the cattle byre in the morning. She picked up the water pot and headed for the well.

“Hello, Anei,” a boy’s voice said behind her in Dinka.

Anei turned. “Oh, hello, Geng. Going to milk the cows?”

“No!” Geng’s brow jutted, making his black face look more sullen than usual. “I’m not a child anymore, Anei. This wet season I’ll go to the cattle camp.”

Anei smiled. “Already? Next you’ll be thinking of taking your first wife.”

They walked together silently. The village was slowly rousing itself around them. Smoke from cooking fires sweetened the moment for Anei.

“Anei,” Geng said, stopping. “When I take a wife, will you… Ah… If I…” He faltered and looked at her nervously.

Anei clicked her teeth. “Perhaps, Geng.”

The boy brightened. He let out a stifled whoop and took the water pot from her hands. “I will take you for my wife, Anei. I will!”

“I said perhaps, Geng, not yes.” They were walking again. “Do you have the bridewealth? It will cost you lots of cattle to marry me.”

“Not yet, but I will by the time we’re old enough. Anei, I…I think you are beautiful. I will have enough cows for you.”

“Then we’ll see.” Anei took the pot from him. “Now, let a girl do her work.”

Geng ran off toward the center of the village, his bare feet kicking up dust made rosy in the morning light.

“Hello, sun,” said Anei softly, approaching the line of girls waiting at the well. “What good luck you have brought me today.”

She stopped, looking toward the edge of the village. Something was wrong. She hadn’t heard anything, but some part of her felt she was in danger. Perhaps it was another lioness driven into the village by the war and famine? Perhaps an Antonov bomber at the edge of her hearing? She clutched her water pot.

A woman yelled, “Jellabah! Jellabah!” the word for Arab. She wouldn’t be shrieking it if the Arabs were coming only to trade. At the same time came the sound of gunfire. Was it coming from all around the village or was that only an echo?

As these were registering on her mind, she saw horsemen break from the brush. Hundreds of horses, ridden by men in head-to-toe white robes and white cloth turbans, appeared as if by witchcraft and thundered toward the village. They shouted and fired their rifles as they came. Swords glinted in the morning sun.

“Wa!” Anei dropped the pot and sprinted toward her hut.

Behind her, the other girls were doing the same, but already Anei could feel and hear horses’ hooves coming from that direction, and she knew the girls would not escape.

Across the wide village she could see the horsemen descending on the outer huts, men on foot following behind, guns or knives in their hands.

Fear gripped Anei’s stomach. She felt horses overtaking her from behind, their harnesses jingling and their riders whipping them with cruel sticks. At the last moment she reached Acol Deng’s tukul, and ducked behind it.

Three riders pounded past her, followed by more than twenty more. Two noticed her and wheeled around, some horrible thought in their eyes. Anei pushed backward, hoping to find Acol’s door, knowing she wouldn’t escape, either.

But a cry arose from the horsemen who had passed. They had reached the cattle pen and were driving the cattle out. The young boys who had been milking them shouted in fear and tried to run. She saw her brother Mabior and others of his age-set being jostled by the cattle, the cows’ curving horns slicing the air like knife blades. He looked terrified. The two horsemen who had spotted Anei now left her and rushed toward the pen.

Anei coiled to sprint for her family’s tukul, but heard something crash in the cattle pen. The stick fences were being pulled down by the horsemen. The cattle spilled out, their high curved horns slashing furiously. She saw Mabior, without so much as a shout, go down beneath the herd.

Mabior!

She wanted to run to him, but what could she do?

Two other boys sprang away from the cattle, but the Arabs were ready for them. Men on horseback knocked them aside. Men on foot grabbed them. As Anei watched, the men held out the boys’ arms and hacked them off.

The boys fell away, but the men held their gruesome trophies over their heads, showering everything with little boys’ blood.

Anei almost fainted. But a crackling sound she knew broke through to her. Acol’s tukul was on fire. The thatch would quickly collapse within the mud walls, burning anything inside or around the hut.

Anei heard Acol screaming inside. She opened the door and found the old woman huddled against the wall, gaping at the roof. Anei pulled her outside. Outside to what?

The cattle pen was on fire now. So were most of the tukuls on the outskirts of the village. Men on horses and men on foot—even men on camels and donkeys—thronged the dirt lanes, shooting and shouting and burning. Cattle screamed and fire roared throatily, but above all the air was filled with the cries of her friends and neighbors.

Anei could think only of getting home. She sprinted away from Acol, heading toward the center of the village. But it seemed she couldn’t take a step without seeing something she had to watch, something her eyes wouldn’t let her miss.

In the distance to her right, she saw Abuk running away from the village, her two oldest children holding her robe, the baby in her arms. An Arab rode up behind her and struck with the end of his rifle. Abuk fell and the man dropped off his horse and fell upon her. She fought with him on the ground and her son, Yak, pulled at the Arab’s arms. Anei could see the other two children wailing, but couldn’t hear them.

Finally the Arab backhanded Abuk, and turned on Yak. He picked up his rifle and struck the boy on the head. Then he shot Yak four times. Anei could see the boy’s body bounce with every shot. The Arab grabbed Abuk’s baby by the leg and cast her through the air as far as he could. She landed on the hard earth and didn’t move. Abuk’s other daughter lay shuddering in a ball, so the Arab left her alone. He tore at Abuk’s robe and then lifted his own and lay over her.

Anei ran again, pausing beside an unburned tukul. Dinka women and children ran by in a pack, fleeing noise and fire like a flock of goats.

She turned back toward Acol’s hut, which was fully engulfed in flame. Three men were there. One was holding Acol. The others were holding two cattle boys each. One of them was Mabior. He was limping and bleeding, but still alive. With a shove, the men forced the boys and Acol into the fiery hut, and held the door shut.

“Mabior! No! Mabior!”

Again she wanted to save her brother. But again she was paralyzed. If she ran out, she would be thrown into the fire, too. But she had to do something. In her mind she ran to the hut, somehow invisible to the men, and pulled Mabior and the others to safety. But when the vision was over she found she hadn’t moved.

Now she did run, but in the other direction. Even as she went, even as their small voices silenced, their piteous screams echoed inside her soul.

Finally, she saw a hopeful sign. Fifteen Dinka men, the paramount chief and his warriors, charged past her, raising the battle cry and brandishing their spears. The chief had his rifle.

They struck the Arab horsemen like a lightning bolt of black muscle and pride. White-robed Arabs fell off their horses, screeching in pain and surprise. Perhaps no one told them the Dinka might fight back. The chief fired his rifle and Jellabah fell. The warriors towered over the Arabs, more than a match for any opponent.

But then more Arabs rode up. And more still. They surrounded the Dinka, until the horses and the dust and the awful energy of the struggle blotted them from Anei’s sight.

She ran.

Her tukul bobbed in her sight. So far it was untouched. She sprinted toward it, her vision blurred by tears. She tripped on something and fell. Gaining her feet, she saw what had tripped her.

A tiny leg. Some Dinka infant’s perfectly formed left foot and knobby knee, dusty from playing on the ground. Was it her sister, Ajok’s? Anei vomited, her stomach no longer able to absorb the images she was force-feeding it.

The sound of men arguing in Arabic drew her attention. It was coming from the direction of her tukul. Two men—one in a jellabah and the other in the uniform of the Sudanese army—were pulling at a woman as if she were a piece of meat. Anei saw that they were arguing over the most beautiful woman in the village. Her mother.

She was naked and appeared half-asleep. She had blood on her face and her cheek looked swollen.

“Ma!”

Anei had taken two steps toward her mother when she was struck by something from behind. As she fell, her mind registered a horse’s heavy hoof clops. Scarcely had she hit the ground, her right shoulder blade burning with the pain of whatever had hit her, than a Jellabah was off his horse and tearing at her red robe.

His turban had come loose and was unrolling around his head. His white robe had a tear at the shoulder. His skin was as black as any Dinka’s, but supposedly he was an Arab and therefore superior. He had a very narrow, ugly face. He mumbled in Arabic and smelled of horse droppings. He held Anei down with a forearm across her chest. With his other hand he tore away her robe and lifted his own. She couldn’t scream. Only a whimper came out.

Then he fell off her, struck by someone else.

Anei scooted away, holding the shreds of her robe over her. The two men struggled on the ground. One was a Dinka.

“Wa!”

She had never seen her father so fierce. The Arab had a long knife, but her father knocked it aside and struck him in the face. The knife came up again, striking her father’s leg and bringing out blood, but it only enraged him. He pounded the Arab’s face until he stopped fighting back.

He stood off the Arab, but then fell to a knee, gripping the wound in his thigh. Anei ran to him. “Wa!”

“Anei!”

“Wa, why is this happening?”

His look was ferocious, his eyes like the eyes of the Arabs’ horses. “They are Baggara Arabs, Anei, riding with the military train.” He gripped her shoulders. “You have to leave the village! Go! Find the SPLA! Bring the rebels here with their guns.”

“No, Wa, I want—”

“Go, Anei! I can’t protect you here. We will all be killed unless you can bring the SPLA with their guns!”

He shoved her toward the east edge of the village, where the thatch fires were already dying down.

“Go!”

As she watched, unable to move, he took the knife from the Arab’s hand and limped toward the men raping her mother.

He fell upon them with such power that Anei was amazed. She saw the knife pierce one Arab’s neck. The man dropped to the dirt, clutching his throat. His jellabah turned dark red.

The uniformed man rolled off her mother, his pants around his knees. Her father knocked him over and they grappled for the knife. Her mother wasn’t moving.

Suddenly the soldier had a small black gun in his hand. Her father stabbed with his knife just as the gun went off.

They fell apart, both moaning, neither able to rise.

Her father’s face settled to the side. His eyes locked onto hers.

Go.

She ran.

The whole village was in flames now, clogged by more men and horses than she had ever seen.

As she ran from concealment to concealment, she saw that the attack had changed. There was less fighting and more stealing. The screams had turned to groans, the gunshots to whiplashes. Men were collecting what food and valuables the village had to offer.

When she reached the last tukul on the edge of the village, she scanned the dry steppe between her and the bush atop the ridge. Far on her left the Arabs were gathering the horses and cattle.

They were also gathering the few Dinka women and children who had been spared. Anei could hear their wailing even over the flames and the hooves. She couldn’t recognize any of the children from this distance, but she could tell they were mostly girls. The Arabs were making the women and older girls carry away the spoils of their own village.

Geng’s brooding face appeared in her mind. Had he been captured? More likely killed: decapitated or burned alive. But maybe he had escaped! Maybe he and others had gotten away into the bush. The thought filled her with energy.

She had to find the SPLA somehow. The Sudanese People’s Liberation Army was her village’s only hope. She had to get them here before the Arabs got away. Nothing could save her village, but Anei would have to be killed before she would let her friends and family and neighbors become slaves.

The crocodile whose jaws gripped her heart thrashed and spun. And suddenly she was no longer afraid. Now there was only fury. Somehow she was going to repay these “Arabs,” these black-skinned Jellabah who raided peaceful villages.

And somehow she was going to do one day what she couldn’t do today—what she should’ve done today—to save poor Mabior.

She bolted for the brush a hundred feet away. The heat of the fires receded. The clomping of the hooves, the shouts of greedy men, the tears of abruptly destitute women all dropped away behind her. She was Anei, avenger of her village, and nothing could stand in her way.

Except something did.

As she neared the brush, an Arab and four boys sprang out of hiding and grabbed her. She screamed and tore at them like a devil. She scratched a face, broke free, ran. But they caught her again. Again she flailed at them. Then the Arab raised the blunt end of his knife and struck her on the head.

* * *

For the second time that day, Anei awoke.

This time, she was moving. Her neck was very sore and her head throbbed. She saw she was draped across the back of a horse, its haunches under her face and knees. Her arms and feet were tied under the horse’s belly. Flies buzzed around her and the horse’s tail swished at them.

Behind her came a line of horses and people—all connected by a rope. Most of the horses bore riders, but some had infants or food sacks lashed to them. She recognized the Dinka behind her. Women and girls from her village, all balancing valuables or supplies on their heads. She saw Abuk, looking dead but somehow walking. Her oldest daughter was tied to the rope ahead of her. No one cried.

Other horsemen rode beside them, herding all her people’s cattle—the source of Dinka wealth and prestige and pride…and marriage. She saw one of the boys who had helped capture her. His face had two bloody scratches on it. Good.

She didn’t recognize where they were. A line of dark green bushes behind them suggested they’d just crossed a river. But which one?

Unless she died or escaped, she was going to become a slave. How then could she avenge her village and her brother? And her mother, her father, and baby sister? She yanked her wrists, but the rope held her fast. The scratched boy rode close and lashed out with a green acacia stick. It stung her bare back like a burn.

Anei turned her face to the sky then. High above her, floating in a perfect blue pool, was the distant sun.

Want To Read More?

Click here to buy Operation: Firebrand—Crusade from Amazon.

Trivia

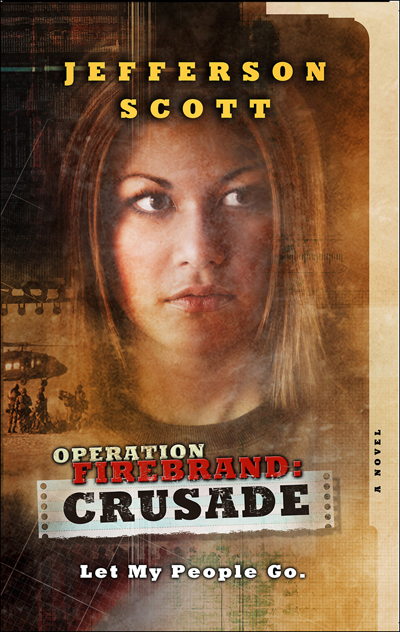

The woman whose face appears on this book cover is supposed to be Rachel, the character featured in Operation: Firebrand—Crusade.

Lookout Design, who did the cover, actually hired a model and brought her into the studio to create this image.

It's the only time any of my covers has ever had a photo shoot. I'm still geeked about it.